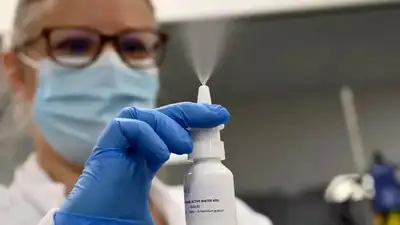

A common nasal spray may help prevent Covid infections, according to new clinical trial results. Azelastine, an over-the-counter antihistamine used for seasonal allergies, has shown antiviral activity against several respiratory viruses, including influenza, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid.

In Germany, scientists at Saarland University Hospital tested the spray on 450 adults, mostly in their early 30s. Half of the participants used azelastine, applying one puff in each nostril three times a day. The other half used a placebo spray with the same routine. All participants tested themselves for Covid twice a week over nearly two months. By the end of the trial, only 2.2% of those using azelastine became infected, compared with 6.7% in the placebo group. The spray also appeared to lower the rates of other respiratory infections.

Researchers are not fully certain why azelastine works against Covid. One theory is that the spray binds to the virus in the nasal mucosa, the moist lining inside the nose, preventing it from entering cells and stopping a key enzyme needed for viral replication. Another possibility is that azelastine blocks the ACE2 receptor, which Covid uses to enter human cells.

Dr. Robert Bals, a professor at Saarland University and lead author of the study, said azelastine could be an easy, over-the-counter option to reduce Covid risk, especially during high transmission periods or in crowded indoor spaces. He stressed that the trial participants were young and generally healthy, and that vaccines remain the most important defense against the virus. Larger studies are needed before recommending the spray for wider use, especially for older or vulnerable populations.

Independent experts praised the findings but noted some limitations. Dr. William Messer, a microbiology professor, said the results are promising but pointed out that using a nasal spray three times daily could be harder to maintain than wearing a mask. Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious disease expert, said azelastine might be useful for people who already use it for allergies, but more evidence is needed before it can be widely recommended as a Covid prevention tool.

Chin-Hong also emphasized the potential of the nasal mucosa as a target for vaccines. Current Covid vaccines do not fully block infection, and he highlighted the need for more research on nasal or mucosal vaccines, like those used for influenza, to prevent respiratory viruses more effectively.

The trial suggests that azelastine nasal spray could be a simple, accessible way to reduce the risk of Covid. Its availability without a prescription makes it easy to use, and its antiviral effects against other respiratory viruses are promising. Experts caution that it should not replace vaccination but could serve as an additional protective measure, especially in high-risk settings. Future studies will help determine how well it works in older adults and immunocompromised individuals, and whether nasal-based treatments can play a bigger role in preventing respiratory infections.